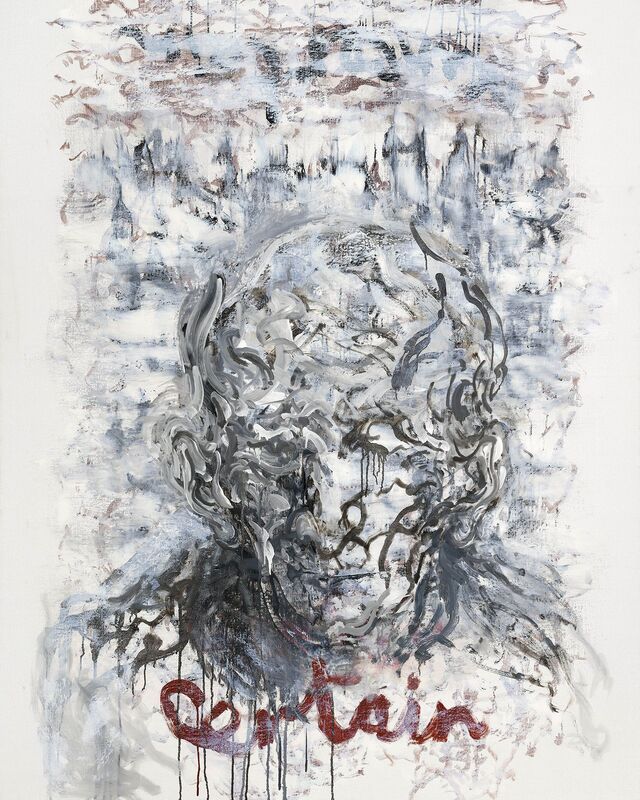

Maggi Hambling's Certain (2017)‘Certain’

The word is scrawled in blood red cursive below a vaporous head of fluid black, white, and blue strokes. What began as an attempt to paint the early morning mist has been transformed into the contemplative lowered gaze of an elderly man. A wash of blue-grey hues remains in Maggi Hambling’s 2017 oil painting Certain, still masking patches of canvas whilst parting to leave others bare. “It wasn’t working and it wasn’t working,” Hambling said of the initial stages of the painting, “and then I turned it upside-down and this image of my father just happened.” Round Revue takes a look at London's must-see exhibitions in 2024, including Van Gogh, Francis Bacon and Yoko Ono

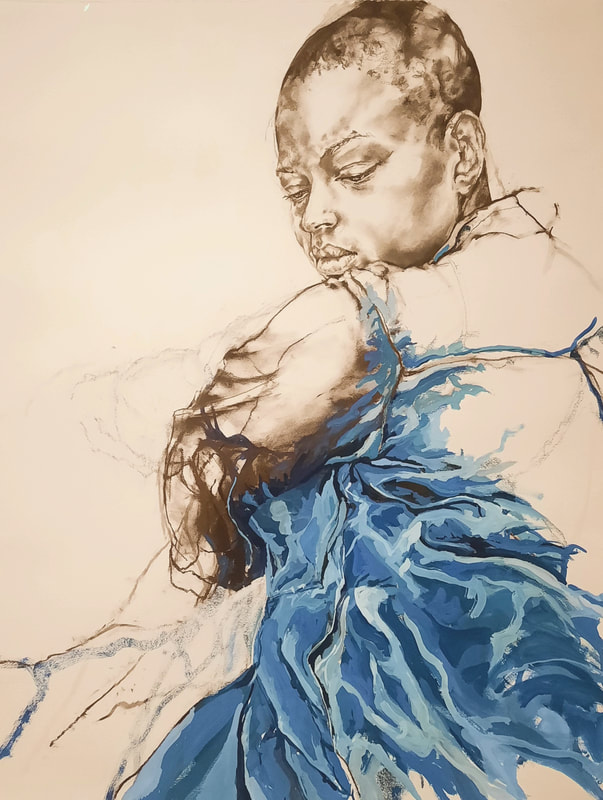

Claudette Johnson: Presence at the Courtauld (29 September 2023 - 14 January 2024)The first monographic show at a major gallery of Claudette Johnson’s work, the Courtauld Gallery’s exhibition is a thought-provoking tour through the two halves of the artist’s career. First coming to prominence in the 1980s whilst still an art student at Wolverhampton Polytechnic, Johnson’s depictions of Black women (whether real or from her imagination) reject the fetishisation and sexualisation that has so often been the context of the black body in Western art. Whether it be Gauguin’s perversions of Tahitian girls (which one walks past in the preceding room’s permanent collection in order to enter Johnson’s exhibition) or the African appropriation of Picasso’s demoiselles, non-white figures have never been out of place in the gallery setting but the context has been always been skewed in favour of the voyeur and exploiter. Johnson explains that even that flawed art of the past inspired her to become an artist, though she seeks to challenge and redefine it with her creations having their own agency rather than caving to stereotypes:

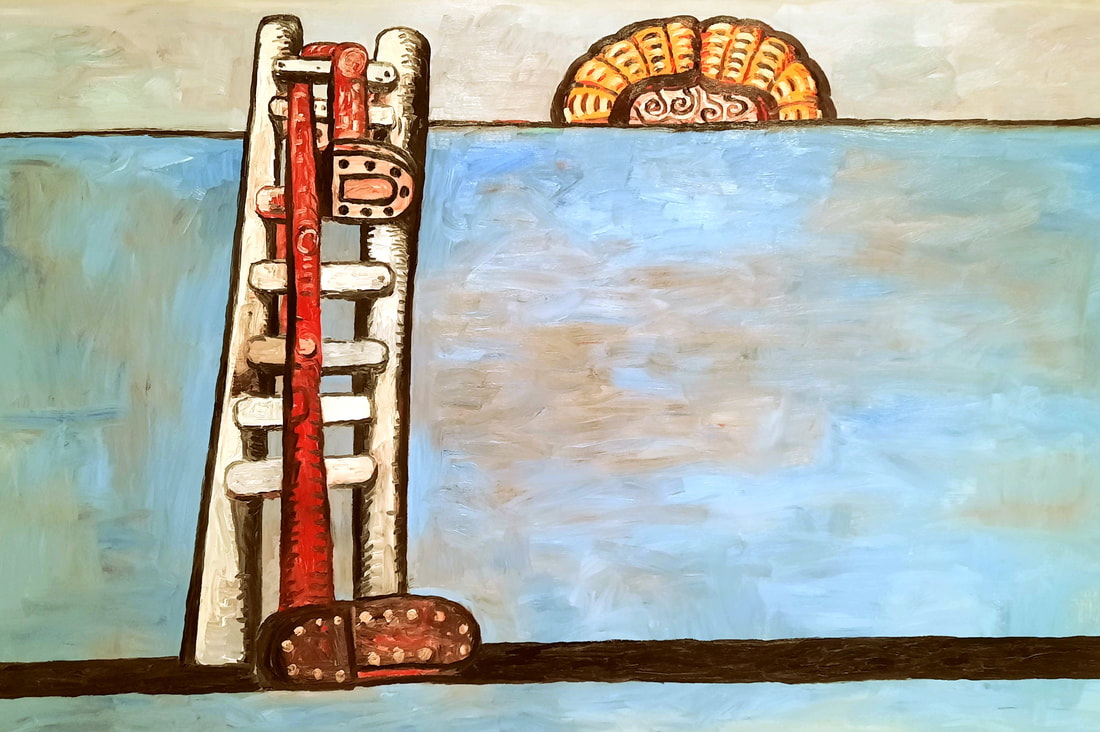

“They are some of the works that first introduced me to the idea of being an artist; they’re foundational, but they always seemed to exist in a space that excluded people like me… I imagine it will raise many interesting questions about what belongs in this space, who belongs here, and who can find a sense of belonging here, in this building.” The first of the two exhibition rooms focuses on Johnson’s early works, including from when she was still studying. One such piece, And I Have My Own Business in This Skin (1982), draws a figure from Johnson’s imagination. In part a response to Picasso’s Philip Guston at Tate Modern (October 2023 - February 2024)Originally scheduled to be shown in 2020 at Washington's National Gallery of Art, Tate Modern, and both the Houston and Boston Museums of Fine Arts, this Philip Guston retrospective was postponed following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May of the same year. It was initially set to be delayed for four years due to its sensitive material and depictions of the Ku Klux Klan, but this was reduced to two years following a petition of 2,000 artists who criticised the museums’ lack of courage to show Guston’s work at this time, with its confrontation with the reality of white supremacism in the modern world.

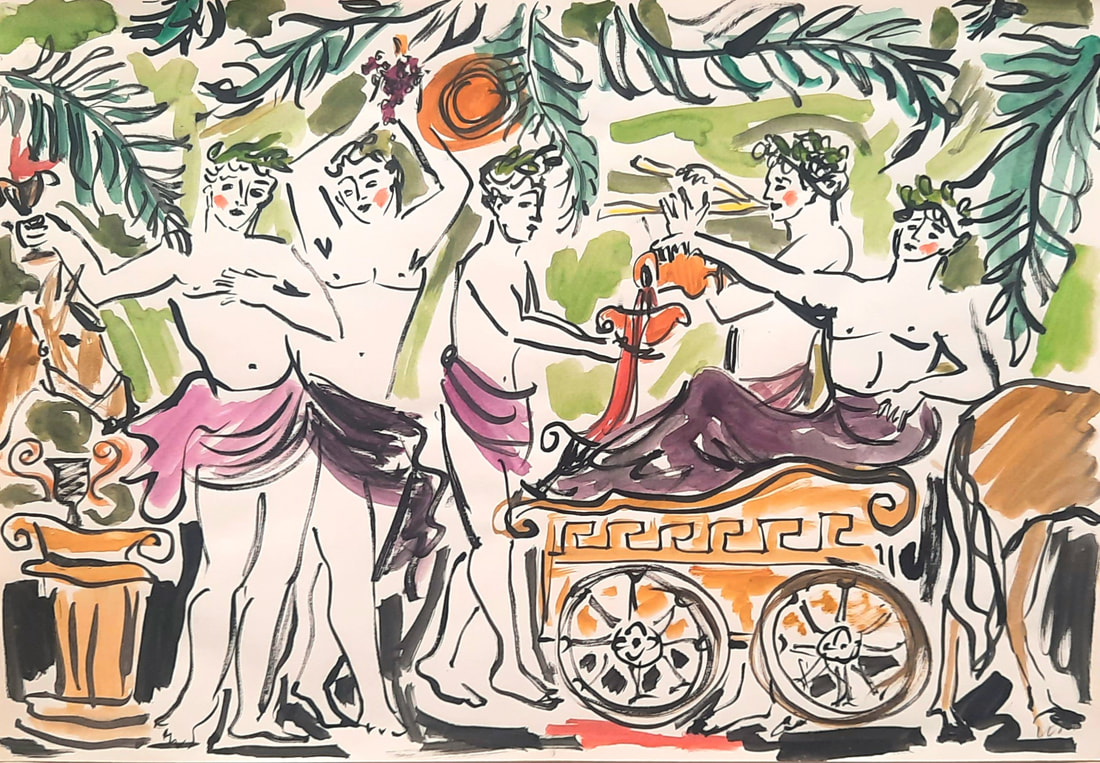

Luke Edward Hall at FRIEZE, No.9 Cork Street (November 2023)FRIEZE played host to the solo exhibition of artist, designer and columnist, Luke Edward Hall, showing works from his collaboration with Seán Hewitt, 300,000 Kisses, a book reclaiming queer love in the myths of the ancient world.

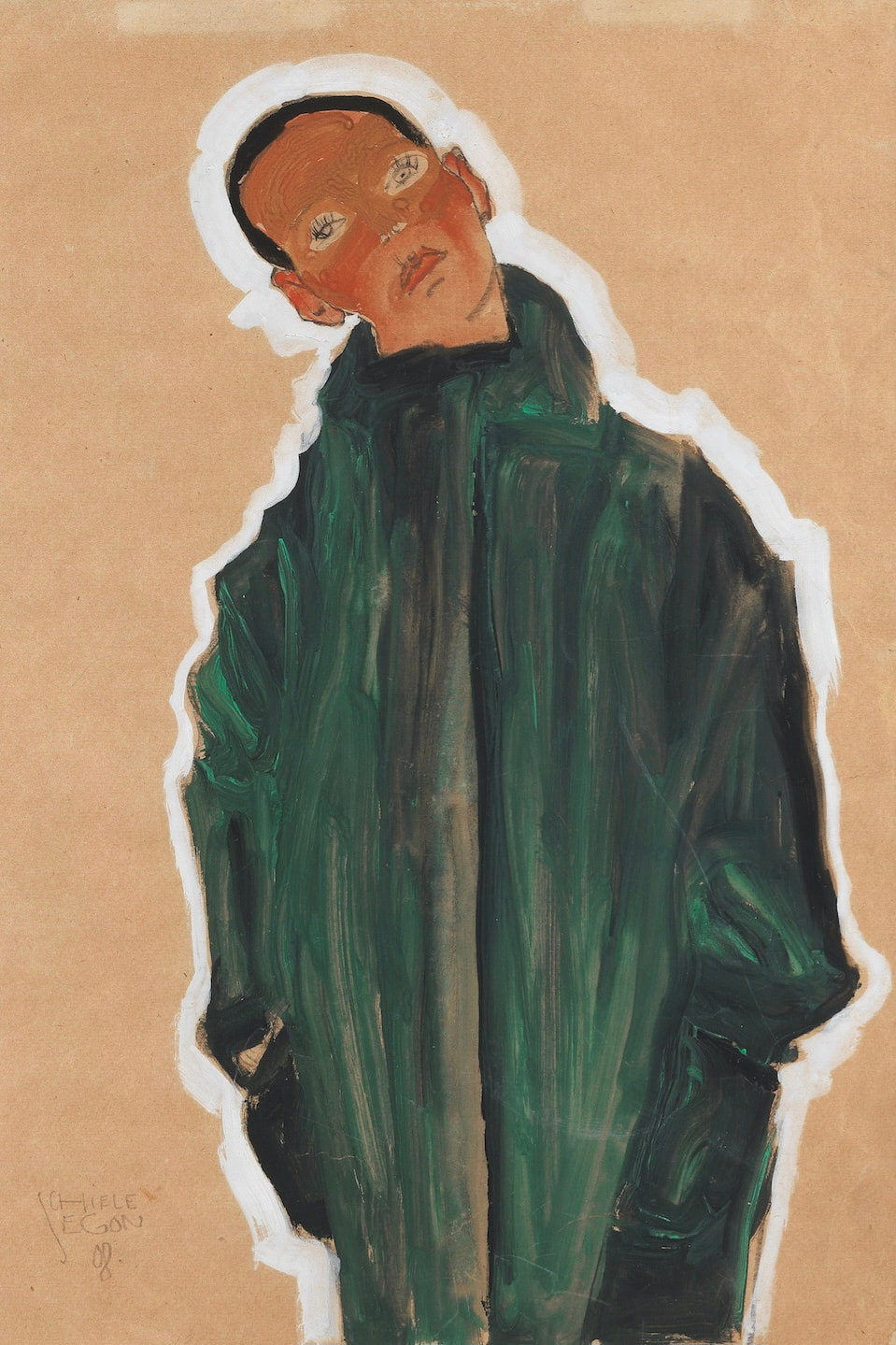

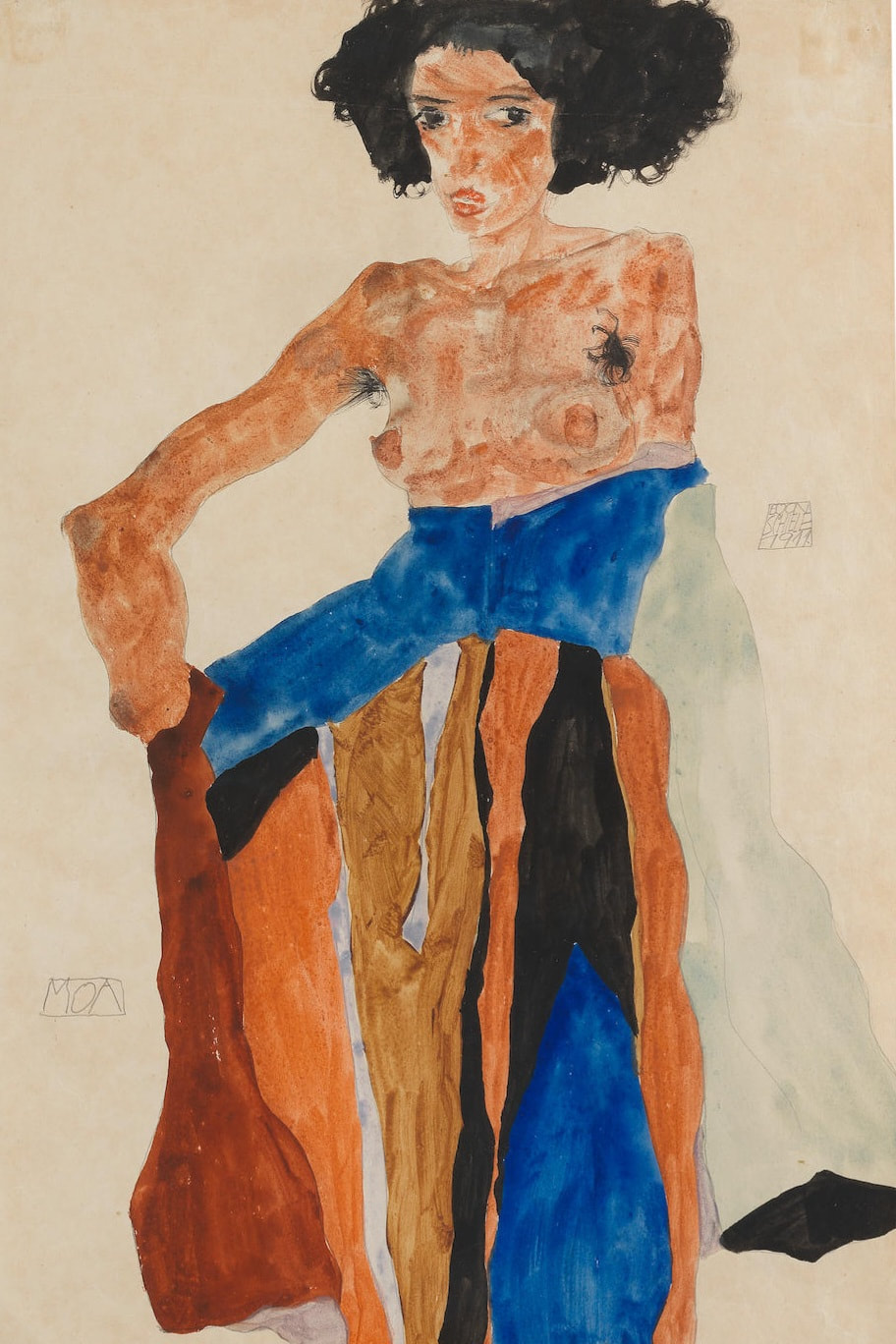

The Unflinching Eye of Egon Schiele, Bonhams, 31 October - 16 November 2022Until mid-November, Bonhams London hosts a small collection of Egon Schiele's works on paper (and one landscape in oil) from 1910 and 1911, when the artist was 20 years old. Representing one of the most extensive collections of the artist's work in the UK, the fifteen drawings and paintings demonstrate his wonder at the human body, both in its beauty and grotesqueness.

Last week I sat in on a Zoom drawing session with model Sue Tilley. Best known for Lucian Freud’s depictions of her in the 1990s (including Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, which set the record for the most expensive painting by a living artist sold at auction when it went for £17 million in 2008), Sue was also prominent on the 1980s club scene where she was a regular at nights such as the Wag Club and Taboo, run by her friend, the performance artist Leigh Bowery. It was Bowery who introduced Sue to Lucian whilst she was working as a benefits supervisor at the job centre. A friend of theirs had attended university with one of Lucian's daughters, who had gotten Cerith Wyn Evans and Angus Cook to model for her father, and they in turn introduced Lucian to Leigh. In fact, they'd introduced the flamboyant Bowery as a ruse to shift Freud away from his neutral, beige pallet (Their words). It didn't work though as Bowery stripped out of his colourful clothes and makeup, and became one of Freud's most successful subjects. "Punctuality was the main thing he looked for in a model," Sue says. "That's why he has so many self-portraits; if someone didn't turn up he'd paint his own reflection.

|

|